Suppose you open Spotify, type “new worship music” into the search bar and begin scrolling away. You’d quickly notice there is no shortage of it available to the average listener. Of course, if you are the average listener, this may be the extent of your exposure to such material. But if you’re a worship leader, you’re likely part of Facebook groups populated by other worship leaders who share setlists and reviews. You’re also probably on mailing lists from resourcing organizations like Multitracks or Praise Charts that highlight certain song releases as noteworthy. Additionally, you may receive periodic requests from certain congregants who are really hoping you’ll lead their new favorite song next Sunday. Regardless, there is a good chance you’re aware there are many worship songs being released into the shared spaces of our churches these days.

Contrary to what our previous release may lead one to believe, there is actually a tremendous variety that coincides with an immense volume of songs currently available to the Church. They come from different churches, from diverse theological perspectives, in various musical styles, featuring people of different ethnicities. (Admittedly, they differ in quality as well.) The onslaught is real. How is the average worship leader to handle these floodwaters?

Based on the research we’ve already released, we submit one obvious technique that, it seems, many are using: worship leaders are identifying, for themselves, some trusted sources. A plausible reason why the overwhelming majority of top-charting songs come from a handful of sources is that, for one reason or another (in one way or another), the majority of worship leaders trust the songs released by those sources, even if they have misgivings about other aspects of those sources.

What if we were to limit our scope of examination to releases just from the “Big 4” (i.e. Bethel, Elevation, Hillsong, and Passion)? Would it feel, to the average worship leader, like a more reasonable volume of songs to consider?

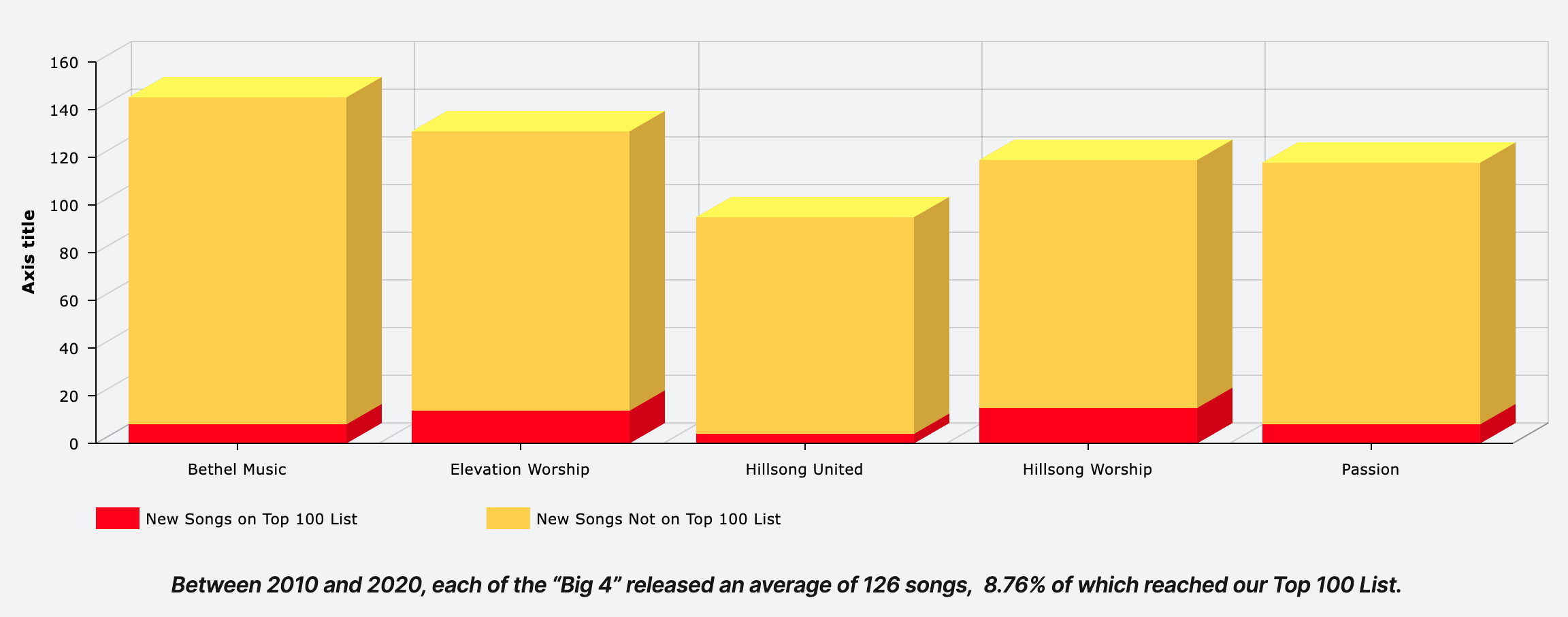

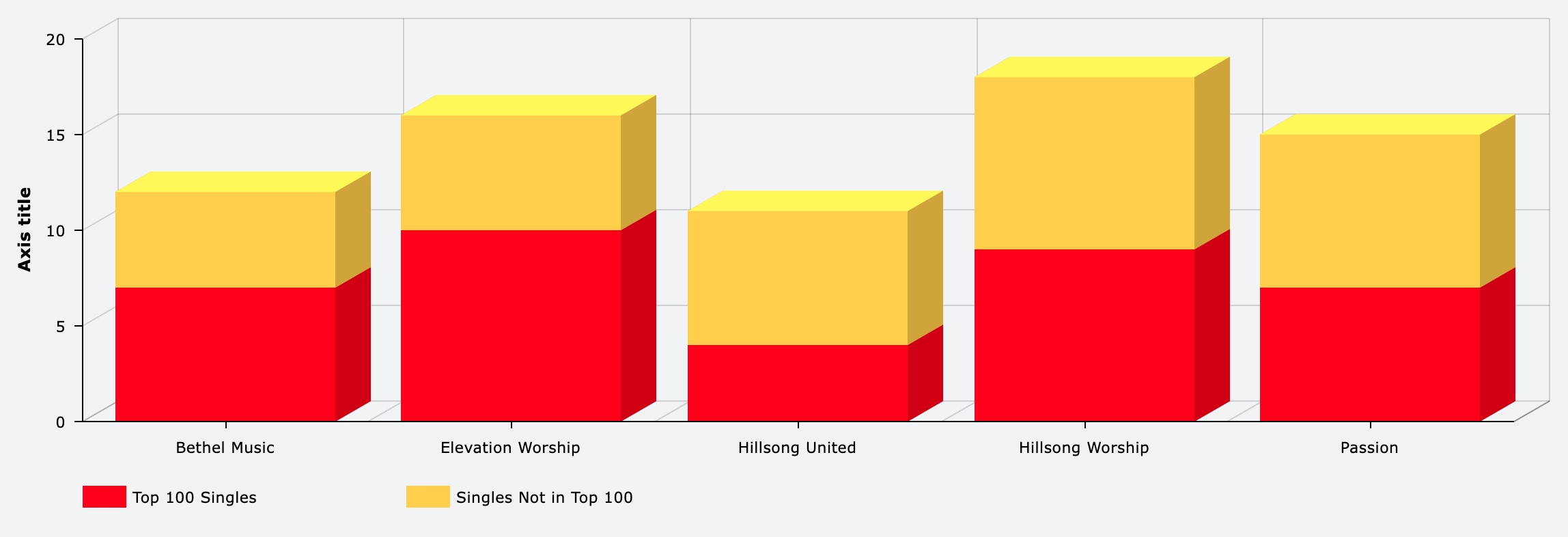

Chart: Total Songs vs. Top 100 Songs (2010-2020)

Between 2010 and 2020, each of the “Big 4” released an average of 126 songs, 8.76% of which reached our Top 100 List.

Chart: Total Songs vs. Top 100 Songs (2010-2020)

Between 2010 and 2020, each of the “Big 4” released an average of 126 songs, 8.76% of which reached our Top 100 List.

During that period, Bethel Music released 145 new songs on 11 albums (not including the manifold releases from Bethel-affiliated artists like Amanda Cook or Leeland, to name just a couple). Elevation Worship released 131 new songs on 10 albums, Hillsong (Worship & UNITED, not including Young & Free) released 214 new songs on 15 albums, and Passion released 118 new songs on 11 albums.

So, each of the “Big 4” released an average of 126 new songs (roughly 12 songs per year) between 2010 and 2020, usually packaged together as albums. Taken individually, then, each of these contributors’ outputs would not likely overwhelm a local worship leader. Taken together, however, it could be difficult for the average worship leader to wade through the 40-50 songs that show up on the Big 4’s yearly albums and determine which ones are more likely to connect with and serve their congregations.

Yet, despite this difficulty, people still manage the selection process. As they whittle down the larger corpus to the few songs they intend to introduce to their own churches, it’s notable that across many geographic, demographic, and ecclesiastical divides, a large number of these leaders end up selecting the same songs from the pool. Thus the top-song charts are born.

Why might this be the case? Are these merely the “best songs” (be the criteria aesthetic or liturgical)? Is there some sort of zeitgeist or shared cultural psyche that leads people to the same selections? Does the Holy Spirit mark certain songs as more in-line with what divine direction is for the Church in a particular season? It is possible that any or all of these answers are at play. Here’s one answer that is almost certainly at play:

Chart: Total Singles vs. Top 100 Singles (2010-2020)

The number of singles released, relative to the number of singles which appeared on the Top 100, was fairly consistent across “The Big 4” from 2010-2020.

Chart: Total Singles vs. Top 100 Singles (2010-2020)

The number of singles released, relative to the number of singles which appeared on the Top 100, was fairly consistent across “The Big 4” from 2010-2020.

During the same time period described above, Bethel Music released 12 singles from those 11 albums, and 7 made CCLI’s Top 100 list, Elevation Worship released 16 singles from those 10 albums, and 10 made CCLI’s Top 100 list, Hillsong Worship & UNITED released 29 singles from those 15 albums, and 13 made CCLI’s Top 100 list, and Passion released 15 singles from those 11 albums, and 7 made CCLI’s Top 100 list.

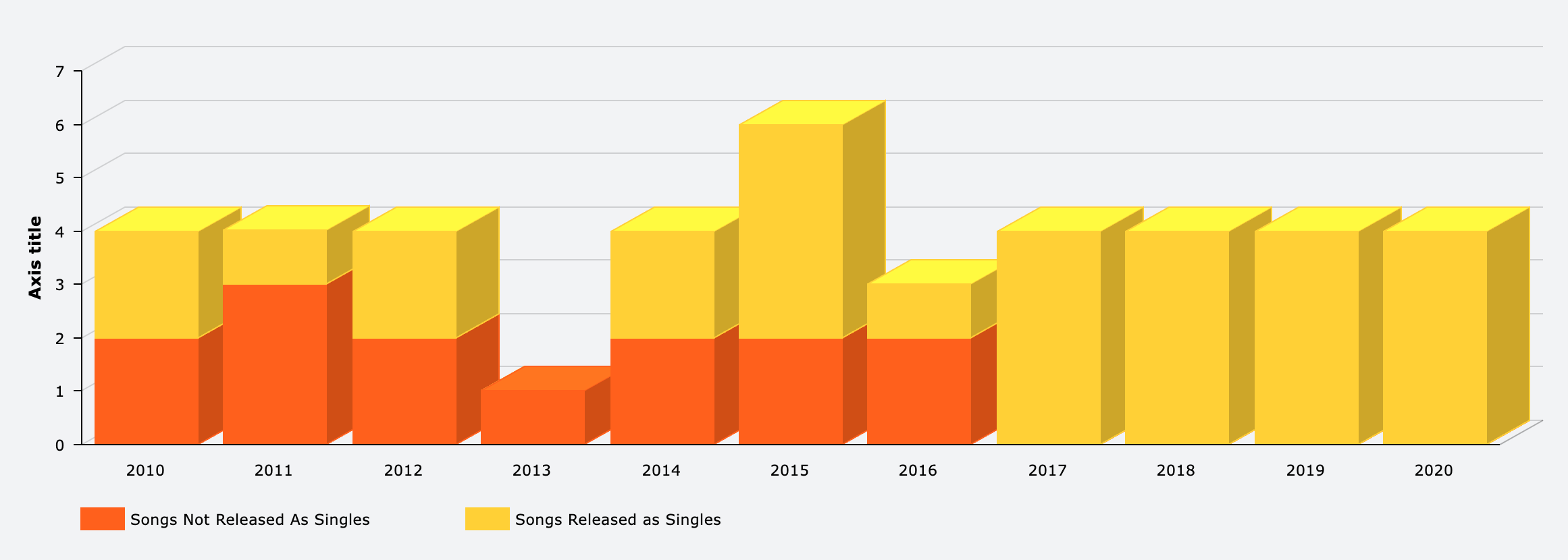

The process of selecting and promoting singles from these worship albums is having an effect. In fact, it’s having so much impact that, since 2017, a staggering 100% of the new songs that made it onto our Top 25 chart were released as singles!

Chart: Percentage of Top 25 Songs Released as Singles (By Year)

In 2017, the percentage of new entries into the Top 25 which were singles jumped to 100% and remained there.

Chart: Percentage of Top 25 Songs Released as Singles (By Year)

In 2017, the percentage of new entries into the Top 25 which were singles jumped to 100% and remained there.

Is it possible these producing churches do not expect or even desire other churches to consider deploying all of the songs released on these albums into their own worship services? A cursory look at the various resourcing websites reveals that they do go out of their way to release charts and tracks for most of the songs on these albums. Why, then, release some songs as singles and not others?

There may be many reasons why, and chief among them would be the evolution of digital music. The digital revolution has significantly impacted the distribution mechanisms for all music. The near disappearance of physical album releases, coinciding with the rise of streaming structures that reward smaller and more frequent releases from artists, has helped create an environment where the cohesive integrity of an “album” is viewed as either a luxury or an irrelevance. By means of example, in November 2016, Spotify re-launched its artist platform with completely updated analytics for artists and the ability to directly promote singles to editorial playlist curators. Additionally, Spotify began requiring artists to select a single song (and only one) when launching an album. The message was clear: Playlists are king. Similar processes became common across the majority of streaming platforms in the following years. That the music we sing in our churches seems to have followed this trend may not be surprising, but it is noteworthy.

These realizations can lead to more questions about the relationship between the promotion of and the adoption of these songs, not to mention the economics of the industrial processes that lie behind them, an area which is being explored by other researchers at the moment. One underexplored effect of the rise of singles over albums is the content restraint of the format. If you release a hymnal, you have potentially hundreds of pages upon which to place songs of varying tone and theme. If you release a 75-minute album, there is space to take worshippers on a journey that includes not only the kinds of songs they may want to sing but also the kinds of songs they may need to sing. If, however, the sustainability of a group or artist is based upon the mass-appeal and adoption of individually released songs, how might that process influence the content of those songs?

We’ll end by returning to where we began, acknowledging that few are likely to go to Spotify and perform the hypothetical search suggested at the beginning of this article. Instead, people are more likely to click on one of the many curated playlists (or let the algorithms take care of the process for them). In such cases, the songs served up are probably not deep-cut album tracks or obscurities but the kinds of songs singled out by artist and label representatives as worthy of attention. Though they won’t necessarily know who singled them out, nor how or why they did so, these unseen hands will continue to impact the songs they hear and thus the songs we sing.

Very soon, our team will begin to release some of the results of our qualitative survey of worship leaders which centers upon their own understanding of these complexities. For updates, sign up for our mailing list at worshipleaderresearch.com or follow us on various social media platforms under “Worship Leader Research.”